TM 5-4240-501-14&P

The air pressure above the fuel in the bowl pushes the

fuel down in the bowl and up in the nozzle to the

discharge holes. At the same time the air rushes into the

carburetor air horn and through the venturi where its

velocity is greatly increased.

The nozzle extending through this air stream acts as an

air foil, creating a still lower pressure area on the upper

side. This allows the fuel to stream out of the nozzle

through the discharge holes into the venturi where it

mixes with the air and becomes a combustible mixture

ready for firing in the cylinder.

A small amount of air is allowed to enter the nozzle

through the bleeder. This air compensates for the

difference in engine speed and prevents too rich a

mixture at high speed.

The story of carburetion could end right here if the

engine were to run at only one speed and under ideal

conditions.

However,

since

smooth

economical

operation is desired at varying speeds, some additions

must be made to the carburetor.

The ideal combustion mixture is about 14 or 15 pounds

of air, in weight, to one (1) pound of gasoline.

Remember that an engine operating under heavy load

requires a richer mixture than under light load. In order

to regulate the mixture, we place in the carburetor a

threaded needle valve with a tapered point which

projects into the end of the nozzle. See Fig. 16.

To adjust the carburetor for maximum power, run the

engine at the desired operating speed, then turn in the

needle valve until the engine slows down, which

indicates a lean mixture. Note the position of the needle

valve, then turn the needle valve out until the engine

speeds up and then slows down, which indicates a rich

mixture, Note the position of the needle valve, then turn

the needle valve to midway between the lean and rich

position. Adjust the mixture to the requirement for each

engine. Remember that too lean a mixture is not

economical. It causes overheating, detonation, and

short valve life. Also, since there is no accelerator pump,

the mixture must be rich enough so that the engine will

not stop when the throttle is suddenly opened. Engines

which run at constant speeds can be slightly leaner than

those whose use requires changes in speed.

THEORIES OF OPERATION

Carburetion

The inset of Fig. 16 shows what happens when the

needle valve is turned too far. A square shoulder is

produced on the taper. It is possible, of course, to adjust

the carburetor with the needle valve in this condition, but

it is quite difficult, because a small movement of the

needle makes a big difference in the amount of fuel that

can enter the nozzle. And, if you do get it adjusted, the

vibration can soon throw it off.

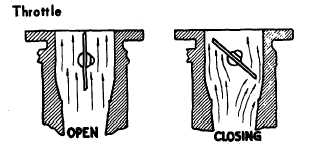

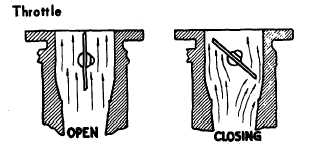

Figure 17.

To allow for different speeds, a flat disc called a butterfly,

mounted on a shaft, is placed in the carburetor throat

above the venturi. This is called the throttle. See Fig.

17.

The throttle in the wide open position does not affect the

air flow to any extent. However, as the throttle starts to

close, it restricts the flow of air to the cylinder and this

decreases the power and speed of the engine. At the

same time it allows the pressure in the area below the

butterfly to increase. This means that the difference

between the air pressure in the carburetor bowl and the

air pressure in the venturi is decreased, the movement of

the fuel through the nozzle is slowed down; thus the

proportion of fuel and air remain approximately the

same. As the engine speed slows down to idle, this

situation changes. See Fig. 18.

At idle speed the throttle is practically closed, very little

air is passing through the venturi and the pressure in the

venturi and in the float bowl are about the same. The

fuel is not forced through the’ discharge holes, and the

mixture tends to become too lean.

Idle Valve

To supply fuel for the idle, the nozzle is extended up into

the idle valve chamber. It fits snugly in the upper body to

prevent leaks. Because of this tight fit, the nozzle must

be removed before upper and lower bodies are

separated, or the nozzle will be bent.

9

14